“This is Kuomintang territory!”

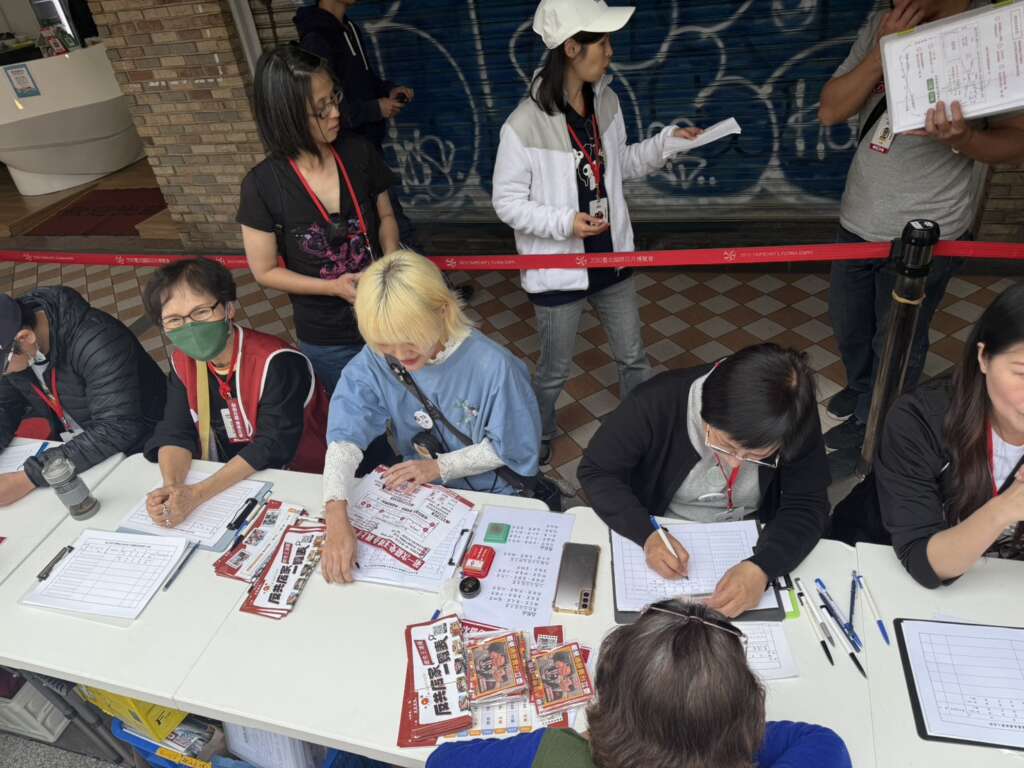

Eric is a jovial and smiling man, enthusiastically guiding us along a busy Taipei boulevard. At the corner of the block, a dozen more people sitting or standing beside a line of tables greet him. They are here to overthrow their local member of parliament. Legally, of course.

Taiwan is going through a recall campaign. In Taiwan, it is possible, if enough voters jump through enough hoops, to ask for an early election in hopes of replacing an elected official before their term expires. It takes petitions, forms, and then a new vote. But it has happened before: if you disappoint your voters in Taiwan, you can be led out of office much earlier than you expected.

And this time, the recall is a nationwide and grassroots movement.

“We did not get what we voted for”

It was little over a year ago that Taiwan went through a general election that brought President Lai Ching-te into office, but also renewed every seat in the parliament, the Legislative Yuan (LY). But this is how short it took for a large bunch of disenchanted voters to go through the arduous process of petitioning for the recall of many members of the LY. So what happened?

“We did not get what we voted for,” says a passerby before grabbing a form and sitting at a table to fill it.

Before we talk to these recall campaigners, let’s break it down:

Taiwan is essentially a two-party country. The Kuomintang, or KMT, is Taiwan’s main opposition party. The other one is the Democratic Progressive Party, or DPP, the party of incumbent President Lai and his predecessor, the popular and famous iron lady Tsai Ing-wen.

Although her vice-president Lai Ching-te managed to get elected as her successor (there is a two-term limit so she was not eligible), he did so with less than half of the total votes (it’s a first-past-the-post election, so he won anyway), because the candidate of a third party (the Taiwan People’s Party, or TPP) got a sizeable share of votes too.

But when it comes to the votes cast for LY members, this lack of absolute majority gave a different result: the DPP fell short of winning half the seats (51 out of 113, with the KMT and TPP sharing the rest).

Now, the KMT and TPP (whose 8 seats prevent both major parties from achieving a majority) are able to block the agenda of President Lai.

And now a nationwide movement is attempting to recall over 30 of them, hopefully to give President Lai’s DPP a majority of seats.

A wake-up call

But if this is the kind of parliament that voters wanted less than a year and a half ago, why are so many eager to change it already, and why would they hope to succeed?

Michael, a retired civil servant, is one of the campaigners. Sitting at a table at the street corner, he explains: “This campaign is kind of a wake-up call… What has changed in the past year is that those legislators from KMT and TPP, they spoiled our political system and checks and balances. They passed several amendments expanding the powers of the legislature that were declared unconstitutional by our court. They’re not happy, so they freeze the nomination of grand justices to the court, so they can pass any laws without checks and balances from the judicial branch because it doesn’t have a quorum.”

Michael concludes: “This is the most important thing happening in Taiwan today: to recall the pro-Chinese legislators,”

This is what we hear all afternoon, from recall campaigners and signatories alike: since the new legislature has been installed, there have been many occurrences of KMT and TPP members appearing as supportive of China. Threats to cut the budget, to lower expenses dedicated to defense or culture, have been met with calls that they were effectively disarming Taiwan in front of its enemy.

“…now people kinda realize, oh my god, they are the CCP people but covered by a democratic mask!”

“After one year, these KMT lawmakers became so obviously so close to China, or more precisely the CCP and this dictatorship that wants to invade us,” says Carol, who acts as a leader of this group. “This is something that we cannot accept, it’s completely unacceptable, so we have to fight. Everyone knows that the CCP cheats, they say something, and they do the opposite… and the KMT does the same thing, they say one thing but once they’re elected they do the other thing. And now people kinda realize, oh my god, they are the CCP people but covered by a democratic mask! So when we discover that, we want to kick them away.”

“The president starts his job in May, but the legislators start at the beginning of the year. So they started pushing a lot of these laws, pro-China laws” says Archo, an event organiser and one of the campaigners. “And we have livestreaming in our parliament so everyone can see it, and everyone was pissed off so we’ve been in the streets since May last year!”

A grassroots movement

Carol welcomes more activists. Microphone in hand, she reminds everyone of what they are fighting for, and keeps an eye on the mood of the streets. Some campaigners hold signs, but most stay behind the tables, ready to inform passersby and assist them in filling the recall form. “We have the confidence that the general public can see what they are doing right now, especially when China is getting more and more aggressive,” says Archo, “so we believe that most voters will be aware of what they have done, and will choose someone that is not so pro-China…”

This is the key to understanding this recall campaign: it’s a grassroots movement.

And this is a KMT-held neighborhood: in theory, these campaigners are in enemy territory. “In a different area you need to find a way to engage with them,” says Eric. “It’s one hundred percent grassroots,” says Carol, “every one of us, we volunteered automatically, we got on the Internet, created a group, and at the very beginning we were like 20 or 30 and we grew bigger and bigger without any politician or party helping.”

“…it comes from civil society, from citizens, voters.”

Archo hammers, “the KMT claims it is not grassroots, because that’s their strategy. But it comes from civil society, from citizens, voters. The people you see here are just ordinary people and we don’t belong to any of the parties.”

Their job is not easy. Carol introduces a fisherman who works at night and, once back ashore at 4 a.m., starts a two-hour journey by bus to join the campaign. The campaigners are all different, ranging from university students to retirees. Some clearly working class and others betraying their wealth through brand-name sportswear. Some of them mention they once were activists for same-sex marriage in Taiwan, bringing field experience in activism. “We have elders who are 80 or 90 years old coming here and supporting us,” says Archo, “and they are very passionate even though they sometimes can’t even walk but they make a stand!”

Read also:

Most of their time is spent helping people sign up: they need to show their identification and fill out the form. It’s repetitive and cumbersome, the same data has to be entered several times, but the mood is happy. Overall, everyone seems to enjoy the experience, not least the campaigners, who sing songs and film each other.

It is not surprising to see DPP-leaning voters signing up. But, as campaigners expected, many are disheartened KMT voters who did not expect their candidates to be so close to China.

On the walls around their stalls, the campaigners put up some posters. A KMT legislator, Wang Hung-wei, features prominently on them, often as an unflattering meme: she is literally the poster girl of what the campaigners are fighting against. As one of the loudest, most visible figures of the KMT in the parliament, Wang has taken the bulk of the campaigners’ anger. Targeting her as a person also has the effect of detaching criticism from the KMT as a whole, sending the message that the enemy is not the entire KMT and its voters, but specific individuals and their precise actions: again, this is not partisan, this is ideological.

More surprising is the presence of a poster featuring Chiang Kai-shek, the former dictator who brought his government to Taiwan when he lost China to the CCP. It is because of him that Taiwan now has to carry state symbols that do not match its reality, such as being officially called “Republic of China” and using its flag, which originally was the flag of the KMT. Although it is now one of several parties, the KMT under Chiang ruled over an authoritarian one-party regime for decades. For this reason, more DPP-leaning voters are averse to using the flag as a national symbol, and loathe Chiang, whose legacy is more contrasted among KMT voters.

Yet, recall campaigners decided to co-opt the image of Chiang and the flag. “Unity is more important,” says one, “many of these KMT voters remember it was an anti-CCP movement!”

This kind of “agree to disagree” for the common goal of keeping China out is rare in Taiwan. In its 35 years of democracy, Taiwan has seen several protest movements such as the famous Sunflower Movement. Each was very much a case of “blue” (the color associated with the KMT) against “green” (the color of the DPP).

“True Blue”

But for this recall, there is a growing discourse that being a “true Blue” is being a KMT voter that opposes Beijing’s rule, and that those KMT politicians or members who favor China are not what being “blue” really means. Years of constant increase of China’s pressure on Taiwan has radicalized even “blue” voters who come to see their order of priority differently: keep China out first, fence against the DPP second.

Still, the campaigners are adamant to welcome everyone while staying free from the influence of parties. “Some of the parties want to ally with us, we say no,” Carol says. “If you want to support us, you can be our friends, but you’re not the boss. Members of our group supported different candidates in the last elections, some voted KMT, or DPP, or TPP. So it’s a mixed civil group.”

It seems the success of the recall took the DPP by surprise. Among the campaigners, those who are the closest to the party say the DPP authorities “thought it wouldn’t work, they saw it as a lost cause.” Now, of course, they are eyeing the results with hope.

“…we are fighting against Xi Jinping!”

The deadline for the collection of signatures varies with each constituency depending on when the process was initiated, but would have passed everywhere by the last week of May. After verification, for those petitions that gathered enough signatures, the votes for recall will take place during summer, and for those who are positive, the re-elections will happen around October-November. “The number of votes required for the petition [to trigger a recall vote in a constituency] is 10 percent of eligible voters,” says Michael, before pointing out that there are 270,000 voters registered in this one. “So ten percent would be 27,000. But yesterday we reached 35,000. Our goal is 45,000, but we are more relaxed!”

Still, the campaigners are only happy on the surface. They know what they are fighting about, and they know who will retaliate if they succeed in giving the DPP a majority at the parliament. As their shift is over, they secure the boxes containing the signatures and dismantle their tables. Before leaving, one of the campaigners says: “we are not just fighting against Wang Hung-wei, we are fighting against Xi Jinping!”